I’ve been in JavaScript development for about thirteen years. I’ve been through Prototype.js, YUI, MooTools, jQuery, Backbone, Angular, and now React (and countless other libraries and tools). I’ve been mostly working on React/Redux browser projects for the last four years on a variety of projects.

This article documents the strategies I use when building browser projects in React/Redux. These practices are the result of: Lots of trial and error. Reaching consensus in various teams. And observing where problems tend to happen. I assume here you’ve at least read the official React docs and Redux docs. If you haven’t yet, do that first.

Nothing in here is a rule; these are high-level guides. Take what’s relevant to you and ignore the rest. Every project has its exceptions. Some projects, React/Redux would be overkill. (I love a plain HTML site.) Or the project requirements are too specific, and React/Redux would get in the way. I don’t love everything about this system. But for a majority of web projects, React/Redux is a decent default.

The “in 2018” part is relevant. Every few months there’s a shiny way of doing things. I’m sure the 2019 version of this article would be quite a bit different.

Please don’t use this guide to try to override a team consensus. I’ve never seen a project fail due to technical choices; but I’ve definitely seen a project fail when the team couldn’t work together.

Why React & Redux

Why use React? There is a sea of options for web browser projects. A few of the key benefits of React:

- React is the most popular option now by far. The largest number of new projects use React. React will continue to have support for at least another 5 years or so. Popularity also means its easy to get help, and there’s a large system of tools supporting React.

- Vue is growing in popularity. Vue uses a similar model to React. Maybe in a few years Vue will become React’s successor, but my guess is React’s successor doesn’t exist yet.

- One-way data flow is a vast improvement over previous systems. The closer to follow this model, the easier the code is to work with.

- The virtual DOM is a performance benefit. It’s an even larger maintenance benefit.

There are many other virtual DOMs… some are smaller in filesize, some are faster. But React is mature, and those other gains are small in comparison to what you get with React’s maturity.

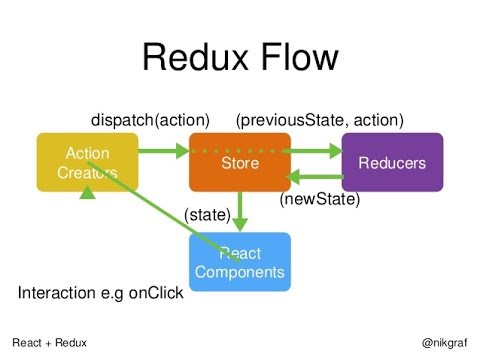

Why use Redux? There’s many options here too for state management.

- Redux is small and easy to understand.

- Redux is the most popular system for state management right now.

- Redux helps keep your changes to state pure, making changes easier to follow and understand.

- Flux, React’s original state management system, gets complicated quickly.

Many other options exist for state managment, MobX likely the most popular. Redux has a problem with boilerplate. Most of the other options have specific ways of addressing this boilerplate. The other options might make sense for your project. My bet is that there will never be a true consensus on the best way to reduce Redux’s boilerplate. Redux is a general solution. And about as specific as we can get while making sure it will work in a variety of situations.

Tiny projects are better off only using React’s component state on the highest component in the tree. You can switch to Redux or another system later.

There’s some other libraries I recommend using. You need react-dom for web projects if you are using React. react-redux is a tiny library that gives a little more guidance on how to integrate React and Redux together. For projects that have more than one route, react-router with react-router-dom is the most popular option. They aren’t perfect, and have changed a great deal in a short time. That said, they’ve come to a good pattern for routing.

Overarching Principles

There’s a few principles I’ve developed over the years working on these projects. These principles can help avoid problems. That said, there’s never an ‘always-right answer.’

Do the boring way first. There’s so many tools and libraries out there in JavaScript world. My general advice is see if you can meet the requirement with a basic function. Do that until you’ve demonstrated that won’t work. If you can use something already built into the browser, try that first. If its specific to React or Redux, try it the way the authors suggest until you know that doesn’t work for your project. (And if you can build your project without JS… don’t assume you need JS at all!)

Functions > Classes. I’m not a functional programming purist. Sometimes mutable data models the problem perfectly. Classes are great for situations where you will need multiple copies of some type of data, and each instance has its own properties. But unless you know you need mutable data or a class in the situation, pure functions are the better default. Functions are simpler to compose, easier to test, and quicker to read.

YAGNI > DRY. Duplicate code is usually bad. But duplicate code isn’t as bad as having overly abstracted code, or wrongly abstracted code. I’ve taken the approach of letting some duplication slide until the pattern is obvious. Most bad abstractions come from trying to be DRY before the pattern is obvious. A little patience is valuable. And sometimes, if there’s little differences each time, you may be better off leaving it ‘wet.’

Single-source of truth > DRY. Redux gives you a single state to work with. Having your Redux state be the single source of truth is more important than being DRY. There will be times you have to decide between having a single source of truth or obeying DRY. Take the single source of truth approach. As long as you have a single source of truth, the pain of not being fully DRY is bearable.

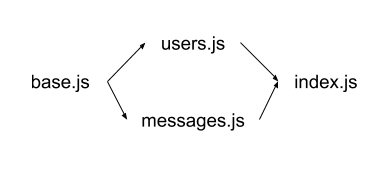

Base → Everything Else → Index. Index is often used as the ‘root’ file name for a directory. I’ve seen cases where other files in the directory depend on index. And others where index consumes the other files. The latter is less problematic. For shared values and functions, I will store them in a “base” file. My other files consume the base file. Then the index file consumes all the other files.

Be consistent with names. JavaScript defaults to camel-case names. Unless you have a good reason to, stick with camel-case as much as possible. You want the name of things to be as consistent as possible. The component, its styles, its filename, its CSS class name, its associated selectors… should all use the same name. It’s confusing when they don’t line up.

Configuring Local Development

Almost goes without saying to use Git for version control from day one.

I would start with **create-react-app**. Unless you have no company boilerplate or other configuration you need to start with. The authors of CRA work on React as well. CRA is an easy way to get started. And there’s an easy opt-out mechanism if your project needs it later. Having seen many boilerplate systems over the years, CRA is the nicest I’ve seen. next.js might make sense for your project too. If you aren’t using a boilerplate, you’ll need to install and configure Babel and Webpack yourself.

Other than a quick demo project, I would recommend using **eslint**. The static analysis tools that come with eslint rival most statically typed languages. I usually opt for the AirBnB ruleset — full for React projects, base otherwise. And I also add in the prettier exceptions. There’s other configurations out there too that might work better for your project.

{

"extends": ["airbnb", "prettier", "prettier/react"],

"env": {

"node": true,

"browser": true,

"jest": true

},

"parserOptions": {

"ecmaVersion": 6,

"sourceType": "module",

"ecmaFeatures": {

"jsx": true

}

}

}

Speaking of **prettier** … much better than arguing with teammates about code style. And it reduces the number of lint warnings you have to deal with. I’ve been using semi-colon free style. In practice semi-colon style makes almost no difference either way.

semi: false

singleQuote: true

trailingComma: es5

Even if you aren’t using React/Redux, I would recommend using **lodash.get**. Heavily. Branch coverage in JavaScript can become a real problem. Having to write and test every possible branch will make your tests much more brittle. JavaScript usually operates in an environment where almost anything can happen. There are rarely any guarantees. lodash.get is one of the tools to help deal with that reality.

// before lodash.get

const userEmail = state &&

state.users &&

state.users[userId] &&

state.users[userId].email ||

''

// after lodash.get

const userEmail = get(state, ['users', userId, 'email'], '')

There’s many styling tool options today. In recent years I’ve worked with sass, stylus, and glamor the most. Every project has different requirements here so I can’t make a general recommendation. If you are starting a new project, I would drop in normalize.css and then have a single CSS file. You can change to something else when the file becomes too large. You could also look at a full CSS system like tachyons or Bootstrap if your project doesn’t have too specific design requirements.

Localization isn’t a solved problem. The browser built-in window.Intl can get you pretty far by itself.

Directory Structure

My directory structure will look something like this:

README.mdpackage.jsonclient.jsserver.jsstate/data/services/middleware/selectors/views/components/views/containers/views/routes/constants/helpers/images/

Root Files

Every project should have a README. Your README serves two purposes: a) documentation for developers and b) marketing. I would suggest your README contains at a least…

- The name of the project.

- A short description. (Who is using this, what are they doing with it, why are they using this.)

- A screenshot, if that’s relevant.

- The build status of the master branch.

- Links to documentation of the tools and APIs your project consumes.

- A list of the directories in the project, and what their intended purpose is.

- A list of top level

npm/yarncommands and what they do.

Your boilerplate may or may not include a **package.json** for you to use. The JS community used to do Grunt and then later Gulp. But now there seems to be a consensus to use the scripts section of package.json. You’ll have development, build, and test commands. package.json now also serves as your home for tooling configuration. I could write a whole article about only this one file, so for this article that’s all I’m going to say about package.json.

{

"name": "messages",

"scripts": {

"build": "# ...",

"start": "# ...",

"test": "# ...",

},

"jest": {

...

},

"dependencies": {

...

},

"devDependencies": {

...

}

}

If your project is client side only — has no SEO requirements — then a single client.js entry to your application will be fine. Otherwise, you’ll need a **client.js** and a **server.js**.

**client.js** will each be responsible for:

- Creating your Redux store,

- Integrating your Redux middleware, and

- Binding your store to React with

Providerfromreact-redux, and - Binding ReactDOM to your actual DOM.

If you are using React Router, then BrowserRouter will be in this file.

const store = createStore(reducer, applyMiddleware(logger))

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', () => {

const container = document.querySelector('#react-root')

ReactDOM.render(

<Provider store={store}>

<Router>

<Messages />

</Router>

</Provider>,

container

)

})

(All code samples in this article are for demonstration. They do not have everything needed for a production experience.)

Your **server.js** file will need to

- Create a new Redux store on each request, which again means binding middleware to the store.

- You’ll need to make any necessary service calls here to generate your Redux state.

- If you are using React Router, then StaticRouter will be in this file.

- You’ll also need your base HTML markup.

- Then you’ll put the finished state and initial React HTML,— rendered with

react-dom/server— into your HTML template.

For actually handling requests, I would recommend Express. Express is easy to use and well supported, and perfect for this sort of situation.

const app = express()

const html = `

<!doctype html>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

<title>Messages</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="/index.css">

<body>

<div id="react-root">{innerHtml}</div>

<script>window.preload={state}</script>

<script src="https://cdn.polyfill.io/v2/polyfill.min.js"></script>

<script src="/index2.js"></script>

</body>

`

app.get(/.*/, (request, response) => {

const store = createStore(reducer, applyMiddleware(logger))

// once the store is filled of data, then...

const myContext = {}

const innerHtml = ReactDOMServer.renderToString(

<Provider store={store}>

<Router location={request.url} context={myContext}>

<Messages />

</Router>

</Provider>

)

if (myContext.url) {

response.redirect(myContext.url)

} else {

response.status(200).send(

html.replace('{innerHtml}', innerHtml)

.replace('{state}', JSON.stringify(store.getState()))

}

})

app.listen(3000, () => {

console.log('serving app realness')

})

Server-side rendering React/Redux is difficult, and more than I can describe in this article. There’s lots that can go wrong with server-side rendering. If you don’t need to do server-side rendering, I wouldn’t. Otherwise, there’s several articles on Medium about how to approach server-side rendering with React. The rule is you need to create everything per request… unless you are caching.

If you have any configuration that you need to have in both the server and client, such as API endpoint URLs or image base paths, I would have that in server.js. Expose it through the HTML document to the browser with an inline script tag. That way, all your configuration stays in one place.

If your needs start to expand on the server-side, I would recommend using the Express middleware pattern. This can help keep your code small and modular on the server-side.

Cross-browser support has been easier the last few years, but there’s still difficulty to know what features each browser is going to support. polyfill.io is an easy way to resolve that issue. You add one script tag to your HTML before your own scripts, and you’re done. Highly recommended.

State

The state is the heart of your React/Redux project. If you master your Redux state, the rest of your application will flow from there. If you get it wrong, you’ll spend lots of time downstream trying to correct the issues.

Think of your Redux state as you would a SQL database. There are three main guides:

- No duplicate data.

- No derivative data.

- Be as flat as possible.

The easiest way I know to abide by these three guides is to write out a state schema. You could have a single file in your state/ directory that describes the keys and default values for your entire state tree. You also add comments to describe what the fields are. And if you wanted to go a little extra, you can also add validation rules to your state schema, though I don’t think that’s usually necessary.

If you have the same fields in two different collections, then you should separate out the shared fields into their own collection. This avoids duplicate data.

Derivative data is data you could figure out from one or more other pieces of data you already have. For example, if you have a firstName field, and a lastName field, you don’t need a fullName field.

When you have nested data, it’s harder to work with later on. As long as you aren’t creating duplicate or derivative data, you want to flatten your schema as much as possible.

The way I structure my state is like:

module.exports = {

global: {

userId: '',

},

users: {

'[id]': {

name: '',

email: '',

},

},

messages: {

'[id]': {

toUser: '',

fromUser: '',

content: '',

},

},

requests: {

'[id]': {

endpoint: '',

success: false,

failed: false,

}

}

}

My state tree has two types: fields and collections.

I have a global section with my flat fields of my state. They only exist on a single level. These fields don’t belong to a collection. Often they are identifiers.

Then I’ll have my collections. Each collection is an object of objects, stored by an identifier. The collections should be mostly flat data. If you have a collection that owns another collection, those should be two separate collections. And joined by an identifier. Think like how you would model relations in a SQL database, and that is the pattern you want to follow. If a collection doesn’t have a natural identifier, you’ll need to generate them with something like UUIDs.

Tal Kol has two great articles going further into state tree design. I would recommend reading those. As long as you are following the three rules above, you can model your state in any way that makes sense to you.

Your state schema can also serve as your default state. You only need a function that will empty out the collections into plain objects. Then you can use that to start up your Redux store in client.js and server.js. The more you integrate your state schema with your code, the more likely it will stay accurate.

function createDefaultState(schema) {

return Object.keys(schema).reduce(

(sum, key) => {

sum[key] = isCollection(sum[key]) ? {} : schema[key]

return sum

},

{}

)

}

For writing your reducers, there’s been a growing consensus around the duck pattern and Flux Standard Actions. I would recommend using those. And your top level reducer can be Redux’s combineReducers.

I’ve worked on projects where every field and collection had its own unique set of actions. I’ve also worked on projects where the same set of actions were available on each field and collection, and all worked the same way. The consistent approach is easier to work with. For each of my “global”, flat fields, I will have two actions: set and reset. The set can work with any value, and reset will return the value back to the default. For my collections, I have seven action types: add one, add many, update one, update many, remove one, remove many, reset. And across collections, these all work exactly the same way. I like to have exactly those seven, so I always know what each collection can do without looking up my reducer.

// state/global.js

function globalReducer(state, action) {

if (action.type === SET_USER_ID) {

return { ...state, userId: action.payload }

}

if (action.type === RESET_USER_ID) {

return { ...state, userId: schema.global.userId }

}

return state

}

// state/users.js

function usersReducer(state, action) {

if (action.type === ADD_USER) {

return { ...state, [action.payload.id]: action.payload }

}

// ... ADD_USERS, UPDATE_USER, UPDATE_USERS, ...

// ... REMOVE_USER, REMOVE_USERS ...

if (action.type === RESET_USERS) {

return {}

}

return state

}

// state/index.js

const reducer = combineReducers({

global,

users,

messages,

})

I make all my action creators the same way, using this sort of function:

const createAction = type => (payload, meta) =>

({ type, payload, meta })

const setUserId = createAction(SET_USER_ID)

dispatch(setUserId('abcd1234'))

If you choose to have consistent actions, you will see the vast boilerplate that Redux generates. I would wait a bit until the pattern is completely clear before trying to DRY it up, and even then a little at a time.

Side note: I haven’t had any positive experiences with immutable.js. Keeping mental track of plain versus immutable data was hard for a single contributor. And impossible for a team. If you’re thinking about that approach, immer seems a bit more reasonable.

Update/Edit 2018 Oct 10: Check out Redux Starter Kit and my Redux Schemad.

Test Data

Having good test data is the most efficient way to speed up development time for almost any project. I can’t recommend it enough. You can use test data for fast local development. You’ll also have a much easier time writing unit tests.

In my projects, I have a directory of data/ with two types: (a) fully written out test Redux states and (b) example responses from all the endpoints I’m going to use.

I will have at least four Redux test states.

- An ‘everything’ state, that shows as many possible combinations of things as possible.

- A null or zero state, which would be what the user first has when they arrive.

- A loading state, that shows what the page looks like while services are loading, and

- An error state, to show what happens when each service has an error.

As your project becomes more complex, you’ll likely need more states of each of these as well as other types of test states.

I like to have an easy way to load up each of test state and render the React tree on the test state. A good way to do this is using a query string parameter. This will make developing the React side of your project very fast. And unit testing your views as well.

I like having at least one sample of each endpoint I will use in the project. These samples will make formatting service responses and the corresponding unit tests very easy. You could also use your sample service responses to validate the real services match your expected data format. I’ve seen some make mock services based on the sample service responses as well. Mock services are not necessary for most projects, but mock services are an option.

Services

There’s lots of ways to make network requests. For one, straight up XMLHttpRequest might work for you. Otherwise, I’ve seen a growing consensus about the browser built-in, Promise-based window.fetch. If you need to server-side rendering, you can find a package to get fetch to also run on the server. (On async/await: Until there’s more browser support, it transpiles heavy… I wouldn’t use it in the browser yet.)

In my services directory, I would have either one file per family of endpoints (GET/POST/PUT/DELETE). Or I would do one file per endpoint, if there is one than one service with several endpoints.

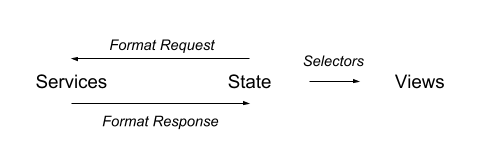

For each endpoint, I have three functions. The top level is the actual service call. Which I name the function something like getMessage, listMessages, postMessage, putMessage, or deleteMessage. The format is {method}{noun}. The pattern here is:

- Format state data to the parameters of the request (optional).

- Update the state to record I’m making a request to this service.

- Make the request, then…

- If the request succeeded, format the response. Then dispatch an action to update the state with the formatted data from the response.

- Either way, update the request in the state to record the request finished.

function getMessages(dispatch, getState) {

const params = formatGetMessagesRequest(getState())

const id = uuid4()

dispatch(addRequest({ id, endpoint: GET_MESSAGES }))

return fetch('/messages', params)

.then(response => response.json())

.then((response) => {

const payload = formatGetMessagesResponse(response)

dispatch(addMessages(payload))

dispatch(updateRequest({ id, success: true }))

})

.catch(() => {

dispatch(updateRequest({ id, failed: true }))

})

}

Formatting the request and formatting the response can get verbose. So I will split those out into separate functions. For example:

- I have a highest function,

getMessage. - I have a function called

formatGetMessageRequest. That takes the Redux state and other parameters. And returns an object of formatted parameters to make the request. The format I use isformat{method}{noun}Request. - I have function called

formatGetMessageResponse. That takes an API response. And returns the formatted response to match my state. That way I can dispatch actions to update my Redux state. The format I use isformat{method}{noun}Response.

function formatGetMessagesRequest(state) {

return {

headers,

body: {

userId: get(state, 'global.userId'),

},

}

}

function formatGetMessagesResponse(response) {

return get(response, 'messages', []).map(message => ({

toUser: get(message, 'toUser', ''),

fromUser: get(message, 'fromUser', ''),

content: get(message, 'content', ''),

}))

}

I’ve seen some use Normalizr to handle the formatting more systematically. I haven’t run into a project where I needed a tool to handle this, but that’s an option too.

Making service requests will likely be the messiest part of your project. As long as you expect service calls to be a little messy, you’ll be much happier.

Redux Middleware

So now you have a state tree, and you have service functions. But how do you know when to call your services? Or send analytics events?

Some developers use lifecycle methods in React — componentDidMount — with local component state. If you’ve already decided your project is complex enough to use Redux, I would recommend against doing this. React’s lifecycle methods and local component state are, well… state. And you already have your state in Redux. So if you use the lifecycle methods or local component state, you are violating the ‘single source of truth’ principle. As a result, its going to be much harder to determine what your project is doing or why you’re seeing the results you are seeing. Especially when you are on a team of people, if there’s state all over the place, its going to be difficult to get everything to work together.

The better solution is to use Redux to store all your necessary state for both the services and views. And to use Redux middleware to make state changes based on other state changes.

There’s some exceptions when you want to use React’s local component state and lifecycle methods:

- You are building a reusable component for other projects to consume. Other projects may or may not use Redux. Even if a project is using Redux, they won’t use Redux the same way.

- You have a demonstrated need to optimize the performance of a particular component.

- Putting all the state for the particular component in Redux and Redux middleware would require lots of non-obvious work. I’ve seen this with tooltips and scroll behaviors, for example.

If you’re not in one of these three categories, I would stick to Redux and Redux middleware for all your state management needs.

So how do we write Redux middleware? Sometimes the direct approach is best. Redux’s authors chose middleware to use the currying pattern, so I recommend being familiar with currying.

There’s two primary ways to think about cascading state changes. One way is to listen to actions as we dispatch them, and call functions that match. redux-saga, a popular library, falls into this category.

const serviceMiddleware = store => next => action => {

const result = next(action)

if (action.type === GET_MESSAGES) {

getMessages(store.dispatch, store.getState)

}

return result

}

The other approach is you dispatch a function that dispatches other actions for you. redux-thunk falls into this category. As do most other “async” libraries for Redux.

const thunkMiddleware = store => next => action => {

if (typeof action === 'function') {

return action(store.dispatch, store.getState)

}

return next(action)

}

dispatch((dispatch, getState) => {

getMessages().then(() => {

dispatch(setMessagesFetched(true))

})

})

Lots of projects are using redux-thunk. When you dispatch a function instead of a plain object, the middleware calls the function. The function has access to store methods getState and dispatch. The access is what redux-thunk provides. Otherwise, it provides no guidance on how to make these state changes. For a single contributor, this is fine. For a team, this may be problematic.

I’ve seen both approaches — ‘listen then do’ and ‘do many’ — work. I have a preference for the “listen then do” approach. My reasons are:

- You can keep almost all state management out of your views. Views only know how to dispatch plain actions and nothing else.

- You end up with lots of little, easy to test functions instead of big functions that are harder to test.

- It’s easier to keep your state changes in one place. As a result, its easier to see the flow of changes.

My own approach is to use my redux-listen library. That said, it isn’t popular by any means. I find redux-saga heavy for most projects, and redux-thunk provides too little guidance. You can also easily write your own Redux middleware that makes sense for your project. I can’t make a general recommendation here, other than it depends on the project.

Selectors

You now have a beautifully written state with no duplicate or derivative data. At some point, you need to take the data in your state and render out your view. That said, the format your state is in is probably not the format you want in your views.

The first thing developers often do is all the formatting in the view.

function Messages(state) {

return (

<div id="Messages">

{ Object.keys(state.messages).map(messageId => (

<ul>

<li>From: {state.users[state.messages[messageId].fromUser].name}</li>

<li>{state.messages[messageId].content}</li>

</ul>

)) }

</div>

)

}

Soon though, the view has so much formatting and logic its hard to read or reason about. The next step is to use connect from react-redux and have a mapStateToProps function. mapStateToProps takes the full state and returns an object that will be the props for the view. You can move your data reformatting into mapStateToProps. Now you have an easy-to-read view and a separate formatting function.

function Messages({ messages }) {

return (

<div id="Messages">

{ messages.map(message => (

<ul>

<li>From: {fromUserName]}</li>

<li>{content}</li>

</ul>

)) }

</div>

)

}

function mapStateToProps(state) {

return {

messages: Object.keys(state.messages).map(messageId => ({

fromUserName: state.users[state.messages[messageId].fromUser].name,

content: state.messages[messageId].content,

}))

}

}

However, the new problem you’ll have is you have many mapStateToProps functions that have duplicate formatting and logic. The solution to that problem is to use selectors. A selector is a function that takes a state and returns a derived value, e.g. state => value. You can combine selectors as well. Most developers will start all their selectors with the word get. You can call these selectors in your mapStateToProps and now you have a view with almost no formatting or logic in it.

function getMessagesNaive(state) {

return get(state, 'messages', {})

}

function getMessagesArray(state) {

const naive = getMessagesNaive(state)

return Object.keys(naive).map(id => { ...naive[id], id })

}

function getMessages(state) {

const users = getUsers(state)

const messages = getMessagesArray(state)

return messages.map(message => ({

...message,

fromUserName: get(users, [message.fromUser, 'name'])

}))

}

function mapStateToProps(state) {

return {

messages: getMessages(state),

}

}

If you want, you can use the reselect library to help compose selectors together. You don’t have to use this library, but I recommend at minimum reading its README to grasp the pattern. Once you have lots of selectors, the library will be more useful to you.

Here’s the list of things you want to take out of your view and put in either mapStateToProps or a selector:

.length+,-,*,\,%,**,in,<,>,≤,≥,==,!=,===,!==,&&,||,?:- Any function that determines logic, like

RegExp.test - Any function that re-formats data, like

maporfilter - … and sometimes

!

For functions that only do like number formatting or localization, I would leave those in the view.

The “sometimes !” comment is that you want to name any boolean values positive. So don’t use not, un-, hide, or anything negative in a boolean name. For example, !hideSection is confusing.

(The name selector is somewhat problematic, as a Redux/Redux selector is not the same as an HTML/CSS selector. It’s an overloaded term for browser development.)

I recommend grouping your selectors by route. So you’ll have a “base” file of selectors across routes. A selector file per route. And an “index” selector file that can combine selectors from the different routes.

Views: Pages, Containers, & Components

You’re now finally at the part of the application that uses React! If you’ve set up everything similarly so far, then this part is a breeze.

To repeat: I would recommend if you are using Redux, almost always write stateless functional components. (See the three exceptions in the “middleware” section.) If you are not in one of those three exceptions, then I would recommend writing simple, props-only functions across the board. That way, all your state information is in Redux and Redux middleware. You have a single source of truth. And your project becomes very predictable and easy to see why you’re getting the view you’re seeing at any time.

You can start with all your views in one, flat directory. As your project grows, I like to split them into three types of views:

- Components: Simple, functional, props-only components. We haven’t attached to state or routes directly.

- Containers: Components we’ve attached to state, but not directly to a route. (Note: If you have several route, you might not have any containers!)

- Routes: Components we’ve attached to a route, and likely also the state directly. (If you are not using a router, then you’ll likely only have one route.)

Routes can consume any view. Containers can consume any containers and components. And components can only consume other components.

function Component(props) { return <div /> }

function Container(props) { return <div /> }

const mapStateToProps = state => ({})

export default connect(mapStateToProps)(Container)

function Route(props) { return <div /> }

const mapStateToProps = state => ({})

export default connect(mapStateToProps)(Route)

// ... a higher-level file

<Route path="/messages" component={Route} />

react-redux will come into play on containers and routes. You want to use connect and mapStateToProps to connect your state to your view. That keeps that stuff out of the view function itself. mapDispatchToProps will help you bind your action creators to your store. In some places, I’ve also had to create a mapPropsToProps to keep my selectors, logic, and formatting out the view.

JSX is the most controversial part of React. I would recommend using JSX. I don’t love the mixture of HTML and JS. It’s always felt weird to me, even years later. But most other projects are going to use JSX. And the tooling around JSX is spectacular. You get quite a bit for low effort by using JSX. I wish the authors of React chose a straight up JavaScript way to handle templating. But that decision is in the past now.

I’ve been on projects that attempted to use form libraries with either only React or with both React and Redux. Unless your form is basic, I would recommend against using a specialized form library. Form libraries often add lots of overhead for little benefits. I would stick to how the authors of React suggest doing controlled component forms. Wait to DRY up anything until you have a clear pattern of duplication.

Auxiliaries: Constants, Helpers, & Images

My projects have auxiliary directories in them: constants, helpers, and images. Sometimes there are more auxiliary directories too.

Constants help you to avoid magic strings. Constants encode the potential values your project will have. If you use constants instead of magic strings, eslint can help you out quite a bit when its time to refactor. Highly recommended.

Helpers are one off functions that don’t fit into other parts of the pattern. They are always specific to your project. I would recommend before creating any helper, check if there is a package in npm land you can use. Especially lodash. (A hint with lodash… you can install each function instead of the whole thing. That saves filesize in the browser.) I would try to keep to as few helpers as you can get away with, but nothing less.

For projects that need it, I’ll have a directory of images. Not much to say about images other than: optimize your images. You’ll get more performance improvement from optimizing images than anything else. Try using SVG, reducing the number of colors, and using ImageOptim. If you only have a small number of images that are vector-y, base64 encode them. This will save on the number of network requests. There’s plenty of articles about saving on size with images.

Tests

I’ve used Jasmine, Mocha/Chai/Sinon, and Jest. There’s more similar than not. If you already have one, I wouldn’t switch. That said, for new projects I recommend Jest. It’s the easiest to set up and get started with, and has everything you need for unit testing built in.

Jest’s killer feature is snapshot testing. Instead of having to assert every value of an object, or JSX nodes, you can write:

expect(result).toMatchSnapshot()

The first time you run that test, it will make a snapshot of the result. If you run the test later and it isn’t the same, you’ll see where the two snapshots differ. If you want to update the snapshot, you can do so on the command line easily.

I can’t recommend using snapshot testing enough. In particular, here’s some places you definitely want to use snapshot testing:

- The results of your reducers in

state/ - The request and result formatters in

services/(If you have good test data, these can be one line tests!) - You can snapshot a mocked

dispatchin your service calls. And it’ll record the arguments and returns each time we call the mocked function! - Anytime you use

getStatein yourmiddleware/. And the mocking and snapshot-ingdispatchtrick works here too! - Most of your

selector/tests can be a single line, if you use your test data and snapshot testing together. - Most of your

view/tests can also be a single line, if you use your test data and snapshot testing together. You can have one test formapStateToProps.And another test for the view that combines it all together.

// Reducer test assertion

expect(

messagesReducer(allState.messages, addMessage(payload))

).toMatchSnapshot()

// Request formatter assertion

expect(formatGetMessagesRequest(allState)).toMatchSnapshot()

// Response formatter assertion

expect(formatGetMessageResponse(getMessagesSample)).toMatchSnapshot()

// Service assertion

const dispatch = jest.fn()

const getState = () => allState

await getMessages(dispatch, getState)

expect(dispatch).toMatchSnapshot()

// Selector assertion

expect(getUsers(allState)).toMatchSnapshot()

// View assertions

expect(mapStateToProps(allState)).toMatchSnapshot()

expect(

Messages(mapStateToProps(allState))

).toMatchSnapshot()

With simple functions, test data, and snapshot testing, your unit tests almost write themselves.

For other tests, you’ll want to use Jest’s mock capability. If you aren’t familiar with how mock internals, I have a video showing how they work. Jest’s system can handle about 90% of typical mocking needs. You can mock both individual functions and entire modules. Sometimes, the old school way works fine too:

test('updates correctly', () => {

const prevLocation = window.location

location = { href: 'https://example.com' }

expect(something).toBe(another)

window.location = prevLocation

})

One of the most frequent things to mock is time. Especially with snapshots, you want your tests to run deterministic.

Another strategy I use is to use call and apply to override the this context. This strategy gets around lots of otherwise tricky test cases.

test('componentDidMount', () => {

const myThis = {}

const result = Component.prototype.componentDidMount.call(myThis)

expect(result).toMatchSnapshot()

})

Given snapshot testing, I’ve found getting to 100% unit test coverage very easy. If it were more difficult, I wouldn’t recommend 100% coverage for most projects. But in this combination, that goal is practical most of the time. If there’s ever a case you can’t cover, you can always put it in a file by itself and configure Jest to ignore that file.

You can do one of:

- Create one big test directory at the root level.

- Create a test directory in each main directory you have.

- Create a test file sitting right next to each file.

I have a preference for 3. There’s twice as many files in each folder, but it’s easier to work with the files as you’re developing that way.

Wrap Up

I can’t cover everything needed to build a React/Redux project in one article. I’ve covered some of the patterns I’ve seen over the years. These are the ways I avoid the most common problems I’ve experienced. I haven’t covered to approach writing styles in this article. Or setting up the tooling required to support a production experience.

A personal note: I hope one day the browsers have efficient DOM element updating built. Something like…

rootElement.updateNodes(newDetachedDomTree)

This would cut the need for many of the tools I mention in this article. When a library gets popular enough, the browsers later get a way to do the same thing natively. I hope that happens here too.

To reiterate: Take what’s relevant to you and ignore the rest. Every project has its exceptions. You might not need JS, or React/Redux! This article is for 2018. If you are reading this any later, the community will have likely already changed some of this.

Thanks for reading. Feedback is welcome!