I’ll admit it: I’m a huge nerd. One of my favorite subjects is learning how to learn. I’ve read and studied on learning science for many years. And I’ve built my own learning platform, Sagefy. That said, I’m no expert — enjoy this outsider’s take on the literature.

In this article, I’m going to sum up what I’ve learned about learning. There’s an entire field of study devoted to the subject, so I can’t include everything. But these eight points epitomize the research. (If this article is too long for you, check out my 10 minute TL;DR version.)

If you’re a learner too, this article is for you. Maybe you’re a student, a teacher, or a lifelong learner like me. Education researchers usually write these from the perspective of a classroom teacher. I am writing from the perspective of an individual, independent learner. These ideas can apply to a classroom, online learning, and everyday life lessons. And come back and review these ideas every now and again… you might find a new perspective you didn’t expect. I always do.

I believe in evidence. Research isn’t perfect. But research is better than the alternative. We all develop theories of learning throughout schooling and working. But not all these theories have evidence to back them up. Take “learning styles” — the theory that each person has a type of learning, like auditory or visual. The idea is pervasive in institutional education. Yet, the theory of “learning styles” does not have evidence to support it. Feedback from learners about their preferences is another illusion. Instead, we need to focus on learning results.

It’s not always easy to pull research into applicable techniques. Articles like this attempt to bridge the gap. These ideas are not new or unique. I am not the first person to say any of these things. While this specific list and order is unique, every idea in this article comes from other sources. I will link where possible.

If my background interests you: Sagefy is the project I’m building on these ideas. Sagefy is an open-content adaptive learning system. Open-content means anyone can create and update learning content, like Wikipedia. Adaptive learning means the content changes based on the learner’s prior knowledge. The combination means anyone can learn almost anything, regardless of their prior knowledge. To learn more about Sagefy, check out this in-depth article.

The greatest opportunity for technology is human learning. We accelerate our progress by using our tools to accelerate our knowledge. We must avoid technology for technology’s sake alone. Technological advances often do not living up to their possibilities. The history of ed-tech shows technology deviating from learning principles. We avoid unnecessary technological clutter by focusing on core principles. I want this article to be a reference for myself as I build and grow Sagefy.

Idea 1: Do One Thing at a Time

“Do one thing at a time” is a long way to say: focus. Remove distractions. Drop unneeded interfaces. Silence background chatter. Don’t multitask: it doesn’t work. Only focus on one lesson of one subject at a time. When we focus, we get more out of the energy we put into learning.

Attempting to learn three new ideas at the same time to solve one problem is going to slow you down. Instead, isolate and learn each idea, and then integrate the ideas to solve the problem.

1.1 Account for the limits of working memory.

Our brain has about 86 billion neurons. Our long term memory appears to be limitless. Our reality is that we cannot remember everything in our long-term memory at one time. What we remember in the current moment, we call working memory.

George Miller in 1956 found working memory limited to seven items, plus or minus two. Decades later, researchers found our brain limits working memory to four items. This rule applies for anything beyond rote memorization. See Broadbent in 1975, Baddeley in 1994, and Cowen in 2001. IQ measurements generally do not impact working memory limits.

We learn by connecting new information to previous known information. (As we’ll come back to in an upcoming section (3.3).) Your current knowledge takes one to three items. That means you likely only have one or two items left for new knowledge. Much of the rest of the points in this article deal with the limits of working memory.

In summary, be realistic about how much information you can put into your working memory. It’s less than you expect.

1.2 Do one activity at a time. Avoid multitasking.

Humans are terrible at multitasking. One study by Clark, Ayres and Sweller in 2005 asked learners to learn both spreadsheet software and related mathematics at the same time. The learners felt overwhelmed. Another 2001 study by Mayer and Chandler found learners overwhelmed learning an entire interface at once. Learners were more successful learning the interface sequentially.

An entire field of study, capacity theory, has explored the idea of how much one can learn at the same time. Many researchers use the Wisconsin Card Sorting Testing to show we can’t multitask while learning something new.

The gist is that trying to learn more than one thing at a time is counterproductive. Instead, it’s much better to try to learn one thing at a time instead of many things at once. Learn one thing, take a break, learn the next thing, take a break, and so on. If you’re feeling overwhelmed, break down what you’re learning into different steps. Then, bring it all together at the end.

1.3 Cut noise: distractions, extra choices, tangents, extra inputs…

A 1996 Mayer et al study found summarizing a lesson, and reducing information, increased learning. A 1998 Harp and Mayer study found that adding interesting bits of information reduced learning. A 2001 Mayer study found increasing the amount of information in a lesson decreased retention. A 2006 Butcher study found simple diagrams work better for learning than realistic diagrams. Finally, a 2007 Mason et al study found wandering minds were not as capable on performing on tasks.

Noise can come in many forms. Noise detracts from learning. There’s auditory or visual noise. There’s noise as extra choices in the learning interface. And there’s noise in the form of tangents of information. For example, one of my goals for Sagefy is to reduce interface noise to keep the focus on learning. Find a quiet, comfortable place to learn where nothing will distract you. Disable social media, put the phone on quiet, close the browser tabs. Get rid of extraneous thoughts, worries, and planning. Allow yourself to focus on learning one thing at a time.

Idea 2: Set & Adhere to Goals

Define small and achievable goals. Then as you learn, check against those goals. Setting specific goals gives the opportunity for frequent wins, which keeps you learning.

If your goal is too large or ill-defined, you’ll have difficulty focusing and lose motivation. You’ll deal with the constant question, “what’s next?” and spend more time on figuring out what to do than actually learning. By setting small and achievable goals, you keep learning.

2.1 Define small and achievable goals.

There are many goal frameworks such as SMART. What the frameworks all seem to share is making goals that are both small and achievable.

Goals and learning are one of the most studied relationships in educational science. A pivotal study in 1979 by Rothkopf and Billington asked students to set small goals before they started reading. This improved reading comprehension. A 2000 paper by Deci and Ryan finds goals are a fundamental psychological need. A summary article in 2002 by Locke and Latham goes into the long history of the research of setting goals in learning. The researchers showed setting goals — specific, challenging, and achievable — improves learning. A 2006 paper by Kivetz, Urminsky, and Zheng found setting small goals increased desired behavior. A 2010 paper by Koo and Fishbach found focusing on remaining tasks — not completed tasks — delivered higher results. In Ericsson’s deliberate practice model, deliberate practice requires frequently setting goals. The other aspects are focus (1.3), feedback (8.1), and appropriate level of challenge (3.2).

You should start each learning session with a small and specific goal. For example, learning all of calculus is huge and not achievable in one session. Instead, set a goal of solving 20 practice problems for the derivative power rule. That is both small and achievable. Often, the more specific the goal, the more achievable the goal is. Losing motivation while learning is common. Setting small and achievable goals helps us to stay motivated. And setting goals helps us to also live up to Idea 1: Do One Thing at a Time by helping us to determine our focus.

2.2 Set goals for both knowledge and skills.

Bloom’s 1956 taxonomy defines six types of learning activities. Knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. (Also see Krathwohl’s 2002 revision.) If we only set goals for knowledge, we miss the opportunity to develop the other parts. For example, a 1989 Chi et al study found that stronger learners explain what they’ve learned in their own words.

One of the most common sayings is learning has no value unless you can apply what you’ve learned. So we need to make sure the goals we set go beyond memorization of facts. Challenge yourself to relate data points to each other. Work on projects that apply the knowledge. Do comparison exercises. Spend time identifying patterns in the knowledge. Present arguments based on what you’ve learned. Going beyond knowledge is important. (We’ll revisit this aspect further in section 6.2.)

2.3 Habitually review your progress against your goals.

Daniel Pink’s Drive shows intrinsic motivation is more powerful than extrinsic motivation. Extrinsic motivation is reward and punishment. Pink identifies three main principles of intrinsic motivation. Autonomy (see Idea 5), mastery (see Idea 6), and purpose (see Idea 7). Checking our progress against our goals grows our sense of mastery. That in turn builds intrinsic motivation.

In Sagefy, as you learn you get to see your progress of how many units you’ve mastered in the subject. And as you go through learning activities, a simple bar shows your progress to mastering the unit.

As you learn, create a way to visualize your progress against your goals. That reminder can help keep you motivated towards learning.

Idea 3: Adapt to Prior Knowledge

The strongest predictor of how much we will learn is what we already know. Prior knowledge is how much we know going into a learning experience. Adapt the learning experience to prior knowledge. When the learning activity pushes us to the right level of challenge, we make the most of our time learning.

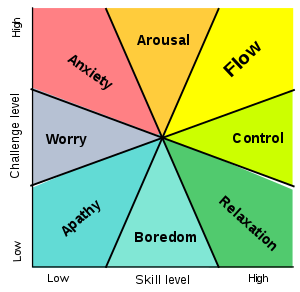

If the content is too easy, we get bored. If the content is too difficult, we get frustrated. Our understanding becomes vague. Either way, we lose motivation. By staying in the in-between zone, we get the most of our learning effort and keep with it for longer.

3.1 Assess prior knowledge first. Focus on areas of weakness.

Dochy, Segers, and Buehl in 1999 found 81% of the difference between learning rates in different learners is prior knowledge. In Hattie’s massive ranking of learning factors, prior knowledge has an effect size of 0.94. Prior knowledge is also the underlying effect of two even stronger factors. Prior knowledge has the largest impact on how much we learn.

Formative assessment is the idea that we should start by testing our knowledge first. Then, we continue to use assessment to learn. Summative assessment is only at the end. A NY Times article highlights the value of formative assessments. In an influential 1972 Bransford and Johnson article, formative assessment activated prior knowledge. The result was that formative assessment is a learning tool itself. A Wininger study tried using assessment both before and during learning activities. This elevated learner comprehension.

We often decide to pick a book or a course for a topic without considering what we already know first. Industrialized education unfortunately suggests all learners are starting from the same place. If you want to learn how to play piano without knowing how to read sheet music, you are in for a difficult journey. Instead, find a means to assess what you already know— and what you need to work on — before you start learning. And, use assessment as you learn to identify areas of weakness and build up in those areas first.

3.2 Stay in the middle and adjust the challenge. Scaffold.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s most famous work is Flow. Flow is a psychological concept of being completely engaged with an activity. We are in “learning flow” when our level of skill and the level of challenge match. Sometimes our prior skill level and the level of challenge don’t align. Then we are anxious or bored. John Caroll’s Minimalism framework also promotes matching the challenge to the learner’s skill level. We can trace this idea back to Atkinson’s 1957 article.

One of the ways to help match prior knowledge and challenge level is to use scaffolding. Scaffolding is the idea of putting on training wheels. At first, provide lots of learning support. Then, remove those supports as the learner’s skill develops. A review by Reiser shows scaffolding is an old and effective technique.

In Sagefy, I measure and update how strong the learner knows the material with each activity. I show the learner activities to choose from and engage with based on those measurements.

We want to avoid learning experiences that are too easy or too difficult. Too easy, and we get bored and waste time and effort on things we already know. Too difficult, and we get frustrated and start to shut down. We want to stay in the middle. Sometimes that means breaking down what we are learning into smaller parts first. That might mean reviewing prerequisite knowledge. We can also scaffold ourselves. Start with simple applications of knowledge, and slowly increase the complexity.

3.3 Connect new information with existing knowledge.

In 1980, Gick and Holyoak asked learners to make analogies connecting their prior knowledge to new knowledge. This improved recall. A 1991 study by Martin and Pressley had students explain how what they already knew applies to new information. This had a dramatic impact on learning. A 1992 review of prior knowledge by Pressley et al looks into the history of prior knowledge. The authors conclude we learn by connecting new information with prior knowledge. A 2004 chapter by Chance, DelMas, and Garfield arrives at similar conclusions.

Before learning something new, start by reviewing related information you already know. Otherwise, you lower the chance to associate those two pieces of knowledge. You reduce your ability to recall the new information when relevant. For example: you are going into a lesson about choosing effective typefaces. You could start by reviewing the different categories of typefaces. Connecting what you already know to what you want to learn is one of the best ways to accelerate your own learning.

Idea 4: Build the Graph

Our memory system works by forming relationships between data. Mastery is the result of a large, deeply-connected graph. We link new information with information we already know. When we focus on organizational knowledge, as we learn we have mental places to put the knowledge.

When we don’t know how experts organize the knowledge before we dig in, we don’t connect the knowledge. Learning becomes mechanical. By learning how to organize the information first, we can quickly connect information. We can use our prior knowledge more. And we get more out of each piece of the graph.

4.1 Learn how to organize the subject before getting specific.

One heavily cited work in educational research is DeGroot’s 1965 “Thought and Choice in Chess.” In this work, DeGroot shows the differences between beginner and expert chess players. Chase and Simon’s 1973 study expands on that work. In that study, beginner and expert chess players differ in organizational knowledge. A 1969 study by Bower et al presented hierarchies of words to learners instead of unorganized lists. This elevated recall. In Reif and Eylon’s 1984 study of a physics lesson, researchers presented organization first. This improved test performance. Another Chi et al study found similar conclusions.

Learn the subject’s organization before you begin to learn something new. That could mean reviewing the Table of Contents in a book before reading it. Or reading the section headings before reading the full text. Review maps and diagrams of how to organize the information. This organizational task can help give structure to your learning plan. Organizational knowledge also helps you to connect appropriate prior knowledge (3.3). And set goals (2.1). And as you learn, you’ll know how the information relates to other areas within the subject.

4.2 Work top-down.

Top-down learning means learning the organization and main ideas first. Then dive into each of those solo. Get deeper as you move further along. Bottom-up learning means learning each component in isolation, then combining the knowledge only at the end.

A 2002 Sun and Zhang study tried top-down processing and bottom-up processing on the “Tower of Hanoi” problem. The top-down approach was more effective. A 2006 article by Lovrich finds use cases for both forms, but generally top-down is more effective. Finally, a 2008 study by Lim, Reiser, and Olina surveyed the whole task first, then drilled down. That was more effective than teaching individual parts then combining at the end.

We know that the brain limits working memory (section 1.1). One strategy to deal with this limit is chunking. Chunking means to group several similar items together. Chunking is one strategy to add a top-down workflow to your learning. A 1980 study from Ericsson, Chase, and Faloon shows chunking nears expert performance for memorizing numbers.

As you learn, try to figure out what the main idea of the lesson is. Then, try to find ways to tie back in each point with the main idea.

4.3 Test your organizational knowledge.

A 1977 Hinsley, Hayes, and Simon study asked students to categorize algebra problems. When students had correct categories, they more often arrived at the correct answer. Having students practice categorizing problems improved performance. A Chi & VahLehn 1991 asked learners to explain and include organizational knowledge. The explanations with organizational knowledge were more effective.

As you learn, find ways to test your organizational knowledge. For example: you could pick out a passage in a text. Then, figure out where that knowledge fits into your schema of the subject. Or you could use an existing diagram and fill in the gaps. You could also try concept mapping; drawing out a map to structure the subject. When you understand the organization, you learn faster and keep the knowledge.

Idea 5: Empower Choice

Autonomy is one of the “three” major intrinsic motivators. Choice fuels autonomy. When we take ownership of our learning through choice, we are more motivated to stick with it. For example, choice can be choosing between one of three units to learn next. Or one of five different formats to learn the same lesson.

If someone forces learning on us, we resent the requirement. Our focus becomes our resentment, not learning. Too many choices can break down our ability to learn too. We focus on making choices instead of learning. And most of us are terrible at making good choices when there are a vast number of options. Instead, the right amount of choice as we learn keeps us motivated and focused on learning.

5.1 Create a system that often allows for choices, in both content and format.

Sheena Iyengar is a prominent researcher in the field of the psychology of choice. She is the author of “The Art of Choosing.” In the book, Iyengar accounts for our fundamental desire for control. The sense of having control can lead to some irrational behavior. Choices can also be motivating as a form of ownership. In a 1989 chapter in “Goal Concepts…,” Bandura finds goals we set ourselves are stronger than goals others set for us.

In Schankenberg’s 1997 dissertation, she found learners practiced more when allowed to make choices. The extra practice improved outcomes (also see the more often cited 2000 republishing). She also found learners reported higher motivation and satisfaction from the course. A 2010 Tabbers and de Koeijer study also found when learners had choice, learners spent more time on instructional material. And as a result had higher transfer.

As you create a learning plan for yourself or others, think about ways to include simple choices. For example, you can choose one of three activities for the same information. Or it could be the format is the same, but you can choose which of four things you would like to learn next. Your learning plan for yourself might look more like a graph instead of a list. That way, given the day you can choose which part to work on next instead of feeling forced into the next step.

5.2 Cut unnecessary choices and reduce the number of options.

Choice can overwhelm. A 2000 study by Iyengar and Lepper looked at the number of options per choice. A limited number of choices improved results and motivation.

Learner choice is likely the most controversial subject in educational research. A paper by Lunts reviews the research. And finds mixed results based on context.

Choice is powerful. Often too powerful. We need to be careful to not overwhelm ourselves with too much choice. Again, the purpose of choice is to create a sense of autonomy and control to drive motivation. The purpose of choice in learning is not optimization.

5.3 Create a recommended default choice.

A learner’s own perception of ability is often inaccurate. A 2010 Zabrucky review highlights this common result in research. Jee, Wiley, and Griffin found learner assessment of ability low for both novices and experts. In a 2004 study by Eva, Cunnington, Reiter, and Norman, past performance predicts results more than learner predictions.

Avoid putting yourself or another learner in a position to make a poor choice. Avoid choices that require learner self-assessment to make an informed choice. One way to avoid these situations is to offer choice with a small number of options. And present a default choice if the learner wants to move on without choosing. You want choice to be about the feeling of control and autonomy, not about optimization.

Idea 6: Dive Deep

Rote memorization is not enough. We must apply knowledge to create results. When we learn not only what, but also how and why, we empower ourselves to use the knowledge we gain. Asking the questions “how” and “why” deepens what we know.

Rote memorization is boring. No one enjoys learning that way. We forget knowledge we learn by memorizing. Instead, we need to focus on how the knowledge works and why the knowledge is relevant. And these are separate goals than “the what”! Diving deep means learning is more interesting and we keep the knowledge for longer. Diving deep means we can apply what we learn and make a real impact.

6.1 Practice.

Getting enough practice is important for skill development. That may sound obvious. But, in school we get this idea that we will learn something by only hearing a teacher recite the information. We also have strong misconceptions about how much practice we need.

One interesting idea here is the Power Law of Practice. Decades of studies have found a power correlation between practice and skill efficiency. In “How I Rewired My Brain to Become Fluent in Math”, Barbara Oakley discusses the importance of mastering the fundamentals. She does this through deep practice before moving on to more difficult subjects. A 1996 study by Sloboda et al found that the amount of practice was an even stronger indicator of results than prior ability. A 1998 study by Healy et al found practice needs to have variety that resembles real application. A 2006 study by Keehner et al found practice reduces ability differences in learners over time. The Foreign Language Institute believes it takes 600–2,200 hours of practice to reach moderate skill with a language. The Language Testing Institute reports a similar range.

You need to build more practice in your learning plan than you might guess.

6.2 Go beyond rote: explain, apply, analyze, and synthesize.

As I mentioned in 2.2, Bloom’s taxonomy identified six core skills. Knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. Craik and Lockhart’s 1972 memory framework shows we need a variety of tasks to build applicable knowledge. A 1997 Schnieder and Shiffrin paper looks at this as well. The authors find what makes fixed and flexible expertise different is the variation of practice. Koedinger & Anderson’s 1998 paper shows learns with higher and performance when practicing a variety of tasks. We find similar messages in McKeough, Lupart, & Marini’s 1995 “Teaching for transfer”.

As you create and update your learning plan, make sure to include a variety of practice. Include exercises that need not only recognition or recall of information. Include exercises that have you to explain, apply, analyze, and synthesize knowledge.

6.3 Build metacognition.

Metacognition — in context of learning — is the ability to evaluate your own learning strategies… and adapt your strategies as you go. Metacognition is a major topic in educational research. There’s way more than I will include in this article, but I’m going to touch on the basics.

Flavell’s 1976 “Metacognitive aspects of problem solving” is an early approach of the subject. He identifies motivation and regulation as key metacognitive capabilities. Several studies have confirmed learners with higher metacognitive ability learn better. A few examples: Palincsar & Brown 1984, Scardamalia Bereiter & Steinbach 1984, and Sengul & Katranci 2012.

As you are learning, every few hours or so, ask yourself a few questions:

- Am I focused on learning? How could I improve my focus?

- What should I be paying attention to?

- Have I done something similar before? Have I experienced something related before?

- How well do I understand this? How difficult is this for me right now?

- Do I understand how to organize this knowledge?

- Do I have a strategy? Is my strategy successful? How many different approaches did I try?

Ask these sorts of questions often. These questions improve your metacognitive ability. And lead you to stronger learning results.

6.4 Space your practice.

One of the oldest studies in educational science is Ebbinghaus, 1885. Ebbinghaus generalizes retention of knowledge to a curve. The stronger the memory, the longer we keep the memory. And the more spaced repetitions of the event, the stronger the memory. Baddeley & Longman in a 1978 found typists who spread out their practice had stronger outcomes. Bahrick and Phelps found in 1987 that Spanish learners who spread out their practice had much stronger retention. Caple’s 1996 paper shows spaced practice improves learning and retention.

Spread out your practice rather than cramming. As the memory becomes stronger, you can go longer times without review. Create a system for yourself, some sort of reminder, to review your knowledge as you learn.

Idea 7: Make It Real

Purpose is another major intrinsic motivator. We need to know not only why the knowledge is important to the subject. We also need to know why the knowledge is important to us. Real-life connection and examples gives the knowledge purpose.

When we remove knowledge from our experiences, we can’t see why we should learn. Instead, review “why should I care?” With this, we can keep our motivation going. And make it easier to apply the knowledge later.

7.1 Check your own reasons for learning.

Purpose is one of Pink’s three intrinsic motivators. A 2004 Robbins et al study looks at learning goals. The study finds goals aligned with intrinsic motivations improve of college outcomes. A 2004 Vansteenkiste et al study also says goals with underlying intrinsic motivation are stronger. A 2002 review of research by Eccles and Wigfield comes to again similar conclusions.

Before you learn, write down why you want to learn the subject. Focus on intrinsic motivation. Yes, extrinsic goals — like getting a job — can be a meaningful goal. But also focus on what that means for you: autonomy, mastery, and purpose. Does getting that promotion mean more autonomy in your day-to-day work? Is that course going to help you help others in some way? Go for deeper purposes.

As you learn, remind yourself of that goal every now and again. And make sure you connect the day’s goal with the bigger picture. It’ll keep you motivated to stay learning!

7.2 Connect material with real-life problems.

Think: problem → solution.

One early theory in learning science is Dewey’s 1916 Democracy and Education. His main thesis is that the mind does not form on its own, but as a social function. This thesis leads to the idea of learning by doing — when we learn in a real context, we deeply learn. When we see what we are learning is real we connect with the material deeper. A 2000 Köhler et al study finds images of concrete nouns stimulated more than textual forms. Problem-based learning is common in health sciences. PBL means focusing on the problem, and learn to find the solution. A 2016 review by Jin and Bridges finds mixed results in this new area of learning research. But learner motivation is higher when we connect the material to real problems. A 2013 Wired article and 2014 NYTimes article shares this idea in story form.

As you learn, try to connect what you are learning to something real to you. An easy way to do this is to ask, “What problem does this solve?” The problem is the context.

7.3 Learn from examples. Use audio, images, video, and interactive.

Listening to lectures and reading textbooks is common. But we know from the research that an example is so much clearer. Examples can be in visual, auditory, or interactive form. A 1985 Sweller and Cooper experiment looked at algebra student performance. The study found swapping some textual description with worked examples is more effective. A 1996 Marcus et al study finds examples lead to stronger understanding of instructions than text alone. Even describing the visual aspects can lead to improved results, as found in a 1997 Kealy et al study. A 1980 Clement study found diagrams to be an effective way to combat misconceptions. A 1997 review by Robertson finds most learners imitate examples as an early strategy. Diagrams are powerful, as a 1987 Larkin and Simon review finds. A 2000 review by Atkinson et al provides guidelines for using examples in learning.

Include examples in a variety of formats in your learning plan. If you get stuck, search for an example using an image or video search engine. Or create your own diagram to help with your own understanding!

Idea 8: Learn Together

When we learn with other people, we can accelerate both our own learning and others’ learning. We can share ideas. Challenge each other’s misunderstandings. And provide and gain feedback.

When we learn alone, we get stuck more often. With no feedback, we miss the opportunity to correct our weaknesses. Without peer accountability, we can let the rest of life take priority over learning. Learning together changes what we learn, when we learn, and how often we learn.

One our key learning drivers is mimicking successful behaviors of others. In Galef and Wigmore’s 1983 article, rats imitated the successful behavior of demonstrator rats. We’re social creatures and learn together.

Not all peer learning and group learning is successful. We need to be careful in how we interact as we learn together to keep things positive and constructive.

8.1 Invite and offer feedback.

Feedback is a powerful and heavily researched topic in educational science. Scientists studied the nuances of asking for and inviting feedback.

Anderson, Corbett, and Conrad in a 1989 study studied computer programming teaching software. The authors found feedback kept learners in the software longer. And improved learning results. Hattie places feedback high several times, with a direct effect size of 0.7. Hattie and Temperly’s own review of feedback in 2007 gets into the nuance. But, the authors find regular and timely feedback improves motivation and learning outcomes. The more focused and task-specific the feedback is, the better the results. Shute’s 2007 research-based guidelines on feedback find similar conclusions.

Feedback isn’t automatic. Unfortunately as humans we’re prone to the bystander effect. We believe someone else will take action. And the more people that are available the less likely we are to take action. So we shouldn’t expect others to provide feedback. We need to ask for it.

In summary, we need to both ask for and offer feedback. Feedback should be timely. Feedback should be as tailored as possible. When you are learning, see if you can find someone who can offer you feedback as you learn. And you can learn as much by offering feedback to others too.

8.2 Be honest and forthcoming.

In Ford’s 1992 “Motivating Humans”, Ford describes supportive and unsupportive environments. Learners have stronger outcomes in supportive environments. Beck et al’s 1996 “Questioning the Author” informed learners about teaching strategy. When learners knew of the strategy engagement increased. In a 2010 Ritchie and Thorkildsen study, researchers compared learners who knew about the teaching strategy to those who didn’t. The researchers found when learners knew, the learners had higher performance.

We learn better when we are honest and forthcoming with each other. When others are honest with us, our trust in them grows. We’re more willing to let down our shield and let in what they know.

8.3 Hold each other accountable.

A 2014 Russell study found accountable peer groups performed stronger than self-accountability. An article in Harvard Business Review by Grenny looked at teams that rely on peer accountability. …rather than accountability coming from leaders. The peer accountability teams have higher performance.

When we hold each other accountable for learning, we’re more likely to stick with it and finish our goals. One strategy you can try is to find a ‘study buddy’ and have regular, recurring check-ups.

8.4 Build consensus.

In a 2002 De Grave et al study, researchers viewed groups with members reporting “unequal participation” and “lack of cohesion.” Those groups did not deliver learning outcomes. A 2012 Walton et al study asked members to believe another group member shared the same birthday. This improved learning outcomes.

We are social creatures, and we are social learners. When learning with others, consensus can drive learning results. The sense of belonging and alignment can help us to learn faster.

Wrap Up

I wrote this article from the perspective of the individual, independent learner. But these ideas apply to the classroom and to training as well!

Think about ways to create an environment where these ideas can flourish. You could even print out this list and hang it on a wall or another place you’ll see it often.

Update: Wondering how to act on these ideas? Check out my “Checklist” article!

Thanks for reading! Feedback on this article is welcome. I intend this article to be a living document. Did you find some new research to support or contradict one of these ideas? Or something could be clearer or more applicable? Let me know by writing a response!

Links for Further Reading

- How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles by Ambrose, Bridges, DiPietro, Lovett, & Norman

- Building Expertise: Cognitive Methods for Training and Performance by Ruth Clark

- Learning How to Learn by Barbara Oakley (Also see her Top 10 List)

- How People Learn by Bransford, Brown, Cocking, & Pellegrino

- Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise by Ericsson and Pool

- Drive by Pink

- Kaplan Checklist

- Pearson Learning Design Principles

Note: Sagefy was shut down in 2025.